Cross-border cooperation in the Western Balkans – roadblocks and prospects

Whilst business-related initiatives continue to drive regional and cross-border cooperation, politics and implementation capacity have failed to live-up to the standards expected by the plethora of international bodies engaged in strengthening this key area.

By Jens Bastian

Regional development and cross-border cooperation in the Western Balkans is one of the key areas of intervention by multilateral international institutions such as the European Union, the World Bank, UNDP, Council of Europe and EBRD (European Bank for Reconstruction and Development). To illustrate, in order to reinforce cooperation with countries bordering the European Union, the European Neighbourhood and Partnership Instrument (ENPI) includes a component specifically targeted at cross-border cooperation (CBC). Some 15 CBC programmes (9 land borders, 3 sea crossings and 3 sea basin programmes) have been established along the Eastern and Southern external borders of the European Union with a total funding of €1.2 billion for 2007-2013.

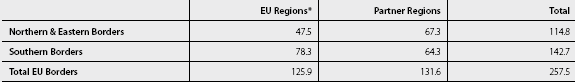

The regions which benefit from CBC have a total population, on both sides of the EU borders, of some 257.5 million citizens — of which 45 percent live in the Northern and Eastern border regions, and 55 percent in the Southern border regions — 49 percent in the EU border regions, and 51 percent in the border regions of the partner countries.

Table 1: Population in the Border Regons in Europe (millions, 2009)

*This includes nine land borders, three sea crossings and three sea basin programmes.

The nature of funding programmes earmarked towards CBC underlines the objective of long-term sustainability. This involvement and multi-level commitment by the international community is a key driver of regional development and cross-border cooperation in the Western Balkans. It is gradually making progress, albeit from a rather low point of departure given the wars and ethnic conflicts of the 1990s.

Regional ownership – the Regional Cooperation Council (RCC)

The Regional Cooperation Council (RCC), (1) established in 2008 and located in Sarajevo, is the most visible sign of new institutional capacity to advance regional as well as local ownership of the policy process. The hope is that regional cooperation in the Balkans can also be delivered by those who are expected to practice and benefit from it. The RCC promotes mutual cooperation and European and Euro-Atlantic integration in Southeast Europe. It focuses on six priority areas: economic and social development, energy and infrastructure, justice and home affairs, security cooperation, building human capital, and parliamentary cooperation. In operational terms, the Heads of State and Government of the Southeast European Cooperation Process (SEECP) (including Greece, Turkey, the western and Eastern Balkans and Black Sea countries) provide the political backing for the RCC’s annual work programme, while the European Commission provides most of the funding. The key aim is to generate and coordinate developmental projects and create a political climate amenable to implementing projects of a wider, regional character, to the benefit of each individual member.

Regional development and cross-border cooperation in the EU context

CBC in the EU context uses an approach largely modelled on structural fund principles such as multi-year programming, partnerships, and co-financing, adapted to take into account the specificities of the European Commission’s external rules and regulations. One major innovation of the ENPI CBC can be seen in the fact that the programmes involving regions on both sides of the EU border share a single budget, common management structures, and a common legal framework and implementation rules, helping to balance partnerships between the participating countries. The European Commission also promotes cross-border cooperation and bilateral development in the Western Balkans through the Instrument for Pre-Accession (IPA) financial assistance tool. This instrument is operational since 2008 and currently applies to all countries in Southeast Europe seeking membership in the European Union. Annual programmes are implemented in cooperation with the international donor community and co-managed with local representatives from the beneficiary countries.

To illustrate the modus operandi of IPA, consider the Annual Programme for Montenegro in 2009/10 with regard to cross-border cooperation. In the priority axis 2, the so-called economic criteria, the EU Delegation in Podgorica awarded €5 million for the rehabilitation of the main rail line Bar-Vrbnica, to the border with Serbia. The beneficiaries of this project are the Ministries of Transport and Telecommunications in both countries as well as the respective railways companies. Given that such transport infrastructure investments require considerable financial resources which the recipient countries do not possess by themselves, the multi-year project is being co-financed with supplementary loans from the European Investment Bank and EBRD totalling €10 million. (2)

A further project illustration in the Commission’s IPA programming cycle for 2009/10 concerns joint cross-border programmes between Montenegro, Albania and Kosovo (3) in the Kukes region. The rehabilitation and improvement of border crossing infrastructure in Morine in the Kukes region bordering Albania and Kosovo has a total budget of €0.46 million in 2009/10. In comparison to the previous example, the sums are small, largely because many implementing regulations are absent in Kosovo. At present, EU CBC programming involving Kosovo’s cooperation with neighbouring countries is being hampered by the ongoing limitations of the international recognition process. (4) These limitations suggest that regional disparities may in fact be cemented despite cross-border cooperation seeking to reduce such differences.

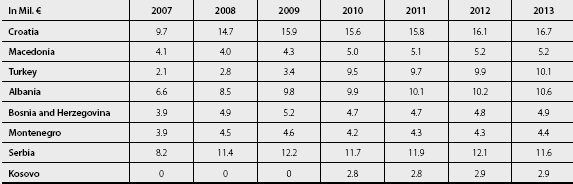

Table 2: CBC Assistance provided by the EU in the IPA Framework 2007- 2013

Source: Communication from the Commission, IPA 2011-2013, Com (2009) 543, 14th October 2009.

A further example underlining the importance of and challenges to regional development and cross-border cooperation in the Western Balkans concerns minority rights and protection. Most countries in the region continue to have refugees and displaced persons from the wars of the 1990s.

In Montenegro, for example, the authorities in Podgorica still need to resolve the status of approximately 16,200 refugees from Kosovo. (5) Cross-border cooperation between Montenegro and Kosovo in this delicate area needs to address such issues as:

- The legal status of refugees and displaced persons (e.g., concerning access to employment for foreigners);

- Construction of accommodation for Roma refugees from Kosovo;

- Of particular concern is the situation of the Konnik refugee camp close to Podgorica; (6)

- Creating legal conditions for the integration of those refugees and displaced persons who wish to remain in Montenegro and acquire Montenegrin citizenship by naturalization;

- The capacity of Kosovo to absorb and re-integrate refugees from neighbouring countries in terms of housing, labour market participation and educational infrastructure. (7)

But while Montenegro and Kosovo may seek to jointly resolve some of these challenges, outstanding issues with neighbouring Serbia can obstruct such bilateral initiatives. Relations with Serbia continue to be disrupted by the Montenegrin decision to recognize Kosovo’s independence. The Montenegrin Ambassador in Belgrade was declared persona non grata in October 2008. A new Ambassador was only accredited to Belgrade in September 2009, almost a year later.

Cross-border cooperation – two encouraging examples from the field

Incremental functional cooperation is taking place on the ground in selected policy-making fields. There are specific examples from the region where cross-border cooperation among countries is starting to manifest itself without primarily being driven by considerations of future political rewards from the European Union. The joint decision by three former Yugoslav republics in August 2010 to form a common railway company aimed at winning back some of the Central European freight business lost during the wars of the 1990s is a case in point.

The commercial objective of the joint enterprise is to ensure rapid freight service along the so-called Corridor X, which links Germany and Austria with Turkey. To date, such transport infrastructure investments had largely by-passed potential rail corridors in the former Yugoslavia, due to a lack of political will to identify actionable projects in this dimension of cross-border cooperation. (8)

A second encouraging example concerns bilateral relations with other countries seeking EU integration. For instance, Montenegro signed an agreement with Albania on cooperation in science, technology and culture in 2009. Concrete steps in such areas as joint border patrols and information exchange against organized crime are taking place. Moreover, Montenegro established a joint working group with Croatian counterparties on resolving property issues and a council on economic relations is holding regular meetings.

Even defence cooperation and joint border police training activities are taking place between countries that a decade ago were at war with each other, while negotiations on agreements in social security are ongoing between various countries in the Western Balkans.

Prospects for cross-border cooperation

Possibly the most important arena for and challenge to cross-border cooperation in the Western Balkans concerns political and institutional arrangements between Serbia and Kosovo. The former refuses to recognize the latter as an independent sovereign state and therefore does not acknowledge the legitimacy of its borders. Meanwhile, the latter itself is having difficulties convincing its own ethnic Albanian population that cross-border cooperation with Serbia may be in its own best interest, in order to advance the international recognition process for Kosovo. (9)

A recent incident in the city of Mitrovica which is ethnically divided between Serbs and Kosovars highlighted the delicacy of the situation and the magnitude of the tasks facing Serbia and Kosovo and the 2,000 strong European Union police mission stationed in Kosovo. In mid-September a French police officer was shot and wounded during clashes between ethnic Albanians and Serbs who pelted each other with stones at the foot of the bridge over the river Ibar that separates the two communities. These clashes occurred after Turkey defeated Serbia in the semi-finals of the world basketball championship.

The clashes underscore the deep divide that runs between both communities more than a decade after the end of the Kosovo war in 1999. It is in cities such as Mitrovica that the feasibility of regional development and cross-border cooperation is most acutely tested in the Western Balkans. Cross-border cooperation is making headway in the field of economic inter-change and public-private investments by the EU, the EBRD and the World Bank. However, it appears that business-related initiatives are primarily driving such regional cooperation. Meanwhile politics and implementation capacity have yet to live up to the specific policies being advocated by the European Union, the Regional Cooperation Council, and other international organizations.

Jens Bastian is Alpha Bank Fellow for South Eastern Europe at St. Antony’s College in Oxford, U.K. He is also a Senior Economic Research Fellow at ELIAMEP (Hellenic Foundation for European & Foreign Policy) in Athens, Greece.

To learn more about TransConflict’s own project to strengthen regional co-operation, entitled ‘Strengthening Inter-Municipal and Economic Co-operation in the Podrinje Region’, please click here.

This article was originally published by Development and Transition, a joint project of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) in Europe and the CIS and the London School of Economics (LSE), and is available by clicking here.

If you are interested in supporting the work of TransConflict, please click here.

To keep up-to-date with the work of TransConflict, please click here.

Footnotes

1. The RCC is the successor of the Stability Pact for Southeast Europe. While its secretariat is located in Sarajevo, the RCC also has a liaison office in Brussels. The Secretary General of the Regional Cooperation Council is Hido Biscevic. For further information consult www.rcc.int.

2. EIB is the financing institution of the European Union. It has provided in excess of €4.5 billion in loan to finance the region of the Western Balkans during the past five years.

3. Hereafter referred to in the context of the UN Security Council Resolution 1244 (1999).

4. IPA regulations (Component II as defined in Article 91 of Implementing Regulations) stipulate that a participating country must be fully capable of assuming the financial, administrative andregulatory responsibilities of carrying out such bilateral projects.

5. For a country totalling roughly 610,000 inhabitants (Montenegro), this is a rather high ratio of refugees from one neighbouring country alone. More than 5,600 refugees from Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina also reside in Montenegro.

6. It is the single largest refugee camp, has received considerable media attention inside and outside the country as well as being identified by the European Commission as a test case for the Montenegrin authorities to identify sustainable solutions according to EU standards.

7. The so-called Sarajevo Declaration process, which aims to finalize refugee returns in the Western Balkans since 2006 is only making limited progress. While participating countries are working on their respective roadmaps, there has been limited discussion of implementation issues on either a bilateral or a regional basis.

8. Instead during the past 20 years such rail corridors had been going through Hungary and Romania.

9. Until September 2010 only 70 countries had officially recognized Kosovo, chief among them the United States and 22 of the 27 members of the European Union. But Serbia, Russia, China, Romania, Slovakia, Cyprus, Greece and Spain have not recognized the sovereignty of Kosovo.

Pingback : Cross-border cooperation in the Western Balkans roadblocks and prospects | Linked2Balkan News