The military, in the barracks and in society

By staging a coup, Egypt’s generals have acted against the grain of an era in which militaries have become less involved in politics. That is their problem.

| Suggested Reading | Conflict Background | GCCT |

By David Kanin

One of the less-discussed elements of the recent round of protests in Turkey is the fact that the Army was such a minor part of the action in Istanbul or elsewhere, and was discussed only in passing by officials and outside commentators. At one point, an exasperated Deputy Prime Minister Bulent Arinc threatened to call in the troops, but his superiors remained silent on his threat and nothing came of it.

This is not a small thing. If such unrest had broken out just a few years ago—or was just believed to be likely to break out—observers inside and outside Turkey would have expected the Army to step in and arrest the politicians. This had happened in 1960, 1971, 1980, and—to sideline the Islamist party of that day—1997. That so many participants in the recent street theater seem not to have considered this contingency worth worrying about as an endgame regarding the activities in Taksim Square marked a major step in Turkey’s democratic development.

As much as they may hate him, the protesters owe this development to Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan. The skill and speed he exhibited after being elected Prime Minister in 2002 in de-fanging what had been among the world’s more politically intrusive militaries has protected not only those involved in the gradual Islamicization of the country, but also those opposed to it. Activists and protesters who under the praetorian structure Ataturk created would have found themselves quickly crushed, now can wear Guy Fawkes masks, launch rocks or Molotov cocktails at the cops, and pose heroically on social media (if not on the cowed Turkish domestic television, radio, and print outlets). Hundreds have gone to jail, but these activists are going to face court proceedings rather than lethal force. This does not mean Erdogan should get a pass on his poor judgment and worse behavior, but it matters that this crisis is playing out in a very different context than used to be the case when Turkey faced a period of unrest.

It is telling that Erdogan, no matter how clumsily he reacted to the protests, did not himself threaten to use the military as a club. Perhaps the Prime Minister thought about the possibility that an unleashed Army leadership might turn on him. On the other hand, after more than a decade in power, he and his party have had time to recruit and promote believers in uniform, and so there likely exist units that would react to orders to restore order by doing so against the protesters rather than against those in power. Maybe these are the forces Arinc had in mind when he raised the issue of military intervention. In any case, the troops so far remain in their barracks, and so it appears the government and civil society now can do battle in courts, elections, and the streets without the institution with the biggest guns weighing in.

Pakistan Likely is Paying Attention

There has been something of a comparative history of the political adventures of the Pakistani and Turkish military elites. Both represent leading non-Arab Muslim societies that have absorbed elements of Western modernity while grappling with the role of Islam In society. Both historically played a major and sometimes disheartening role in their countries’ politics. Both militaries now find themselves excluded from interfering even when the politicians appear autocratic, indecisive, or inept.

There are major differences, of course. Turkey’s Kemalist military traditionally was muscular in its secular ideology and uniformly opposed to any injection of religion into its doctrine or operations. This was not the case in Pakistan, where during the 1980s General and Strongman Muhammad Zia ul-Haq was a confirmed believer and was determined to meld military rule and an Islamic state. Zia arguably played a decisive role in opening the door to the subsequent Islamist revival in a country whose founder, Mohammad Ali Jinnah, was as skeptical of traditional religion (even in the context of insisting on a Muslim Pakistan) as was Turkey’s Ataturk.

Still, the removal of Pakistan’s corps commanders from the country’s politics is contemporaneous with Turkey’s political de-militarization, a fact likely noted among general officers in both places and worth some attention. Erdogan has put some officers in jail via the so-called Ergenekon scandal, while Pervez Musharraf, who had parlayed an unsuccessful military provocation against India at Cargill into a coup, finds himself on trial for treason after meekly returning home from exile. The retreat of Pakistan’s military command from politics was one factor permitting recent elections in Pakistan that enabled—for the first time—an electoral and relatively peaceful replacement of one civilian leadership by another.

To an extent, this involves a wider phenomenon. Even given the military background of Venezuela’s recently deceased Hugo Chavez, Latin American militaries also currently are much less inclined to intervene in politics than they were a couple of decades ago. No one that I am aware of has raised the possibility of military intervention as a factor in the ongoing protests in Brazil. In part, the explosion of social media may well be affecting calculations by anyone in uniform anywhere who thinks he can overawe electronically inspired public resistance to old kinds of interventions.

What About Egypt?

Egyptians just went back into the streets and howled (most with approval, many in anger) in the latest episode in that country’s version of direct democracy. The latter, despite hyperbole from activists and some pundits, should not be confused with rule of law and does not necessarily lead to representative democracy.

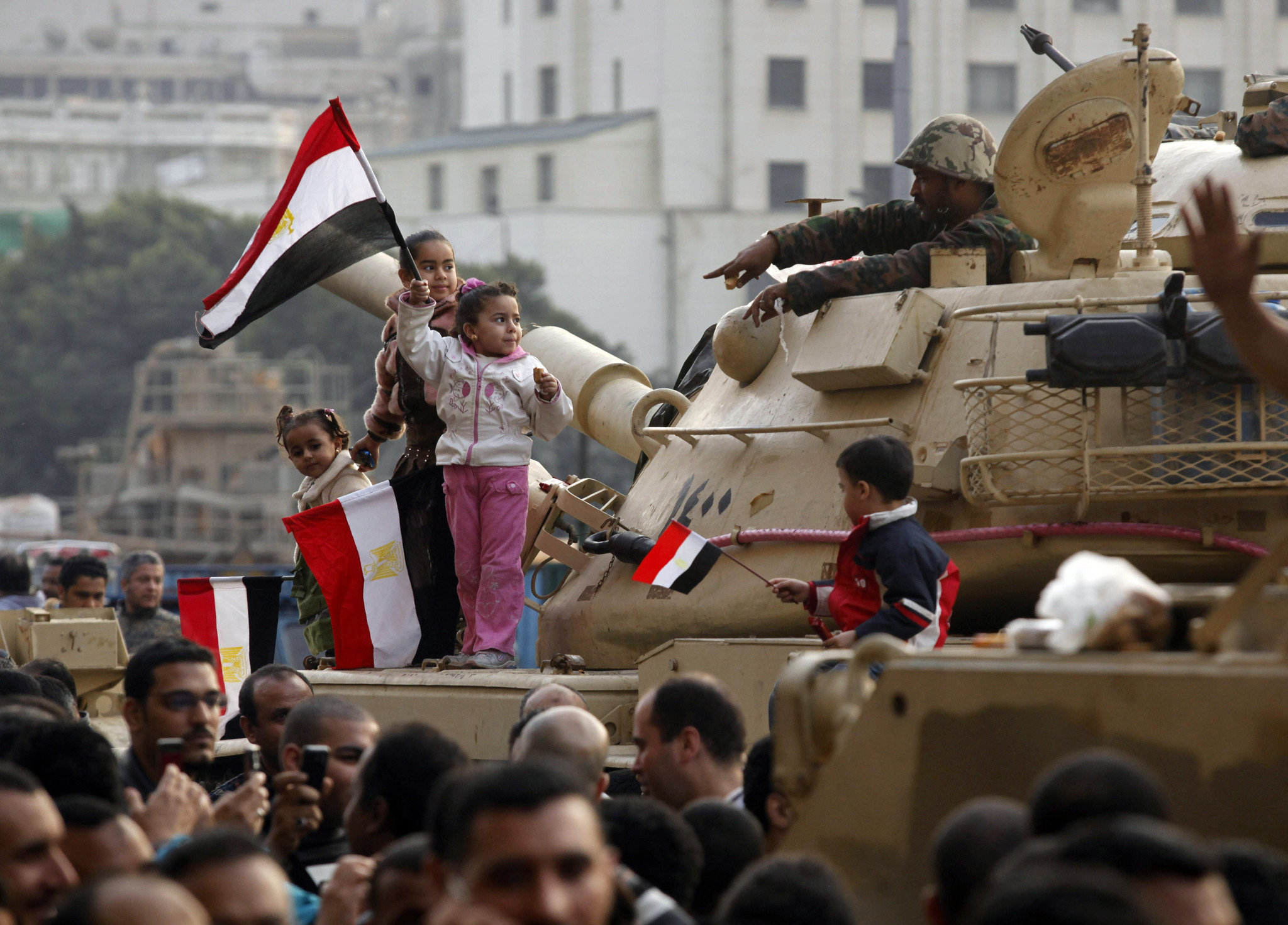

All sides appear largely unafraid of the military’s intervention. During the uprising of 2011, Egypt’s military, far from removing itself from politics, played a crucial part in enabling the downfall of Mubarak. It midwifed—not without mistakes and misjudgments—a transition to a politics that seems to be one part religious and one part civic (whether they are equal parts remains an open question). For a short time, Defense Minister Tantawi seemed to be the most important figure in the country, but—sort of like the English General Monck in 1660—quickly realized he could not (or did not want to) seize power. Tantawi contented himself with administering affairs only until elections could be held. He left when newly elected President Morsi told him to.

The coup in Egypt clearly contrasts with the political impotence of the militaries in Turkey and Pakistan, but some of the same issues are at work. The Egyptian military’s behavior demonstrates that it considers it a priority to retain its positive social status—especially among secular activists. In the run-up to the protests, Defense Minister al-Sisi said troops would be ready to hit the streets to protect citizens—a specter President Morsi’s opponents greeted with approval rather than fear. As the violence built, patrolled the protests as on-site buffers, but the army gave all sides 48 hours to settle things or face the prospect of the military imposing its own “roadmap.” But when then-President Morsi rejected this ultimatum, and secular leaders spoke out against a coup, the Army initially backed off, clarifying its commitment to social peace and political dialogue. It consulted with prominent religious and opposition figures before stepping in. This is not 1952—or the Algeria of the 1990s—Egypt’s generals understand that they cannot organize politics under circumstances of deep division and a complete lack of political leadership. On 3 July, al Jazeera quoted a military aide: “Today only one thing matters. In this day and age no military coup can succeed in the face of sizeable popular force without considerable bloodshed. Who among you is ready to shoulder that blame?”

The military in Egypt, more than its counterparts in Turkey or Pakistan, remains an important economic player. Even given the changes made since 2011, military industries remain active across a wide range of economic sectors. They reportedly are involved with civilian as well as military production. This activity makes Egypt’s military a patronage network, which affects its social role differently than the “kinetic” assets other armed forces have as they assess the societies they sometimes have trampled on. The still-developing institutions and political processes of Egypt’s government permit the Egyptian military to retain its material influence despite the fact that its generals have much less direct influence over politics than did Tantawi in the first months after the overthrow of the Mubarak regime.

The Army’s political and economic role makes it the only coherent institution in the country, aside from a Muslim Brotherhood that failed to make its initial electoral victory stick. The secular parties lack credible leaders and have not demonstrated an ability to more than take part in bringing down unpopular governments. Youthful activists put out breathless rhetoric on social media, but likewise seem unable to do anything other than draw large numbers of people to the Agora (perhaps they should get their largest totals into the Guinness Bok of World Records). Military leaders likely do not want to take responsibility for country’s enormous problems. At this writing, no one else seems capable of doing so either.

That is the generals’ problem. They have no better idea than did Morsi about how to deal with Egypt’s economic problems and social fissures. There is no political, religious, or other figure they can turn to who can unite the country. The activists and foreign governments and NGOs will be full of advice, but have little useful or thoughtful to offer. Al-Sisi’s best option is the same as was Tantawi’s—get out of the way as quickly as possible, before the mob (and that term describes precisely the human waves that have dominated the Egyptian Agora since January 2011) turns on them.

The Army also will work to prevent any link up between Egypt’s ongoing instability and a more conventional military problem. So far, Egypt’s police and armed forces have proven incapable of managing security threats in the Sinai. The generals have had to swallow criticism surrounding the unrestrained activities of traditional Bedouin raiders and the more recent appearance of jihadists looking for a safe haven and a base from which they can threaten Israel and build a threat against Egypt itself. There also is the question of how Egypt’s military perceives the Sadat-era treaty with Israel—but that is the subject for another discussion.

What is the Military’s Appropriate Social Role?

Service in a country’s armed forces does a lot more than provide generals with troops they can order into battle against external enemies or into the streets of restive cities at home. Militaries everywhere provide the important function of socializing young recruits into their societies at large. Training often is designed to impart social and ideological values as well as basic fighting skills. Tito’s Yugoslav National Army was supposed to help create Yugoslavs out of teenagers from the Federation’s various nationalities and ethnic groups. Its disproportionately Serbian officer corps skewed things badly enough that some non-Serb officers (Franjo Tudjman, for example) reacted by adopting disparate nationalist stances. The institution as a whole collapsed as quickly as did its Yugoslavia itself. (Nationalists—largely but not only Serbian—had no problem arming co-nationals as the situation deteriorated). Tito followed the Communist template in relying on his secret police rather than the military for internal security.

By way of contrast, the traditional political culture of the United States had no place for a corporate military structure. From 1775 until the Cold War, the US Army would almost start from scratch each time it had to fight someone, and then virtually dissolve pending the next war. The famous Second Amendment to the Constitution—the one that protects individuals’ rights to gun ownership—was crafted at least in part due to mistrust of European-style standing armies. This attitude changed dramatically after the onset of the open-ended Cold War rivalry with the Soviet Union, which for the first time presented Washington with an apparently permanent ideological, cultural, economic, and military adversary. The National Security Act of 1947 created the country’s first permanent, muscular national security structure. The decades that followed killed the traditional “isolationist” wing of American politics (Rand Paul personifies the first serious effort to revive it since the political passing of Robert Taft). Americans have come to lionize their “warriors” in a way that—in my view—would surprise and, perhaps, displease their 18th century forebears. Instead of socializing military recruits into society, celebration of the Military through patriotic songs and ceremonies socializes society toward martial values.

In their own ways, Turkey, Pakistan, Egypt, and other countries will continue to fashion military establishments that reflect their societies’ social trajectories as much as they perform traditional security and defense roles. At present (Egypt only partially excepted), there appears to be a general tendency for them to play smaller roles in domestic politics now than a few years ago. This could be a promising development, in part because it means the politicians cannot rely on a “man on a white horse” to backstop politics if civilian authorities cannot establish (or, in Erdogan’s case, restore) credible legal, political, and economic structures and policies. It only “could be” promising because so far—in the Balkans as well as the Middle East—self-proclaimed activists, self-seeking social entrepreneurs, and other elites have proven either rapacious or incapable of organizing constructive politics.

David B. Kanin is an adjunct professor of international relations at Johns Hopkins University and a former senior intelligence analyst for the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA).

The military, in the barracks and in society – By staging a coup, Egypt’s generals have… http://t.co/Tys6hFNUmE #Egypt #MiddleEast

The military, in the barracks and in society – TransConflict http://t.co/Zin2IxhGI4