Waging war on poaching – the war on drugs revisited?

In the face of the failed militarisation of the response to drug trafficking, is it appropriate to apply a similar tactic to tackling the poaching problem?

| Suggested Reading | Conflict Background | GCCT |

By Sean Mowbray

Wildlife trafficking has risen on the political agenda, of that there is no doubt. Previously marginalised and the concern of few inside government circles it has risen up the agenda on the back of links to organised crime syndicates and terrorist organisations. This article will seek to question whether in the face of the failed militarisation of the response to drug trafficking whether it is appropriate to apply a similar tactic to tackling the poaching problem.

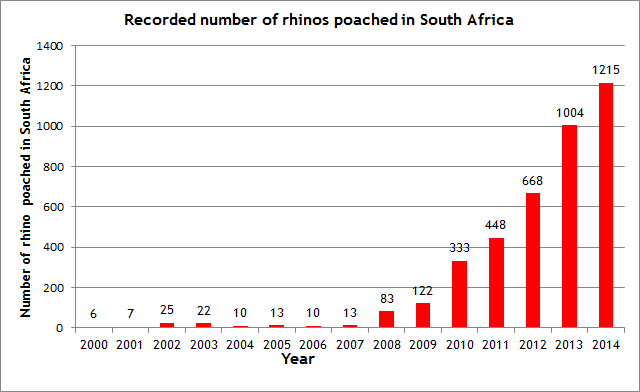

The story of poaching in 2014 was largely confined to the plains of Africa where ‘charismatic mega-fauna’ roam. South Africa in particular has seen seven consecutive years of rampant poaching that has the brought its rhino population ever closer to the brink. Newspapers and media channels frequently covered the plight of the rhino and elephant populations. Making use of high-tech equipment and weaponry poachers have easily been able to exploit a combination of poor enforcement, a lack of political will, widespread corruption and the sheer vastness of the African plains. Although serious in itself to focus solely upon the mega-fauna is to undersell the seriousness and scale of wildlife trafficking. It is an illegal trade estimated to gross around $20billion per year for. This encapsulates much more than ivory and rhino horn.

Ivory trafficking is immensely profitable but in terms of quantity it is minimal. For instance the pangolin is considered to be the most widely trafficked species in terms of bulk. Its value may not be as high as ivory but is funding organised criminal groups in much the same way.

Source: Save the Rhino

The international response the wildlife trafficking problem has been somewhat predictable. The prevalent recourse towards prohibition when dealing with such morally charged issues is one that is deeply rooted in history. In an echo of the fifty year war on drugs there has been a highly militarised approach that has sought to combine new technology, such as drones, to patrol and eliminate poachers. In African countries calls for ‘shoot on sight’ policies have been trialled in an attempt to protect elephant populations and military units have been deployed to enforce these measures. Western intelligence services have also been given the remit of snaring high profile traffickers using the same methods learned tackling drug trafficking. In opting for the militarised option states have risked kindling a ‘war on poaching’. To do so would ignite the same inexorable firestorm that has already been seen through the approach to drug trafficking. For years this has hindered frequent attempts to reform the chosen approach as it is a system which is fundamentally rooted in maintaining the illegality of drugs.

For many years the US drove its foreign narcotics policy with a reckless abandon that sought to punish and squeeze traffickers and cartels with brute force. In Afghanistan, Bolivia, Columbia, and most recently Mexico the militarised approach resulted in many human catastrophes and left the final outcome largely unaltered. Drugs are still widely available and some studies suggest that purity has increased over the years, while the actual street price has decreased. The response is based upon a fundamental misunderstanding of the nature of organised criminal elements. By retaining a structural flexibility that allows adaption to outside pressure, such organisations develop loose connections designed to maintain a fluid response to law enforcement pressure. The seizure of a shipment or the arrest of an associate can often be of minimal effect to the wider operation. It is a tendency in government circles and the media to see the stereotypical patriarchal Mafia style organisation as driving illegal trafficking. Instead organisations develop loose functions to protect themselves from law enforcement. The latter understanding has driven the anti-drug trafficking policy makers and it is now being applied to wildlife trafficking.

By understanding the actual nature and dynamism of organised crime structures the appropriateness of militarisation as a method for tackling wildlife poaching and trafficking becomes much less attractive. By eliminating single poachers, whether by imprisonment or death, there will be an abundance of disenfranchised individuals willing to take their place. This is a scenario which has been repeated throughout the course of the war on drugs. By fixing the response to wildlife trafficking in a similar manner the international community is locking itself into another perpetual conflict which will punish those who seek to engage in illegal activities rather than attempting to assuage the extenuating circumstances that drive people to this extreme action.

It is of great significance that wildlife trafficking is now being viewed ever more seriously on the world stage. Increased exposure has allowed renewed funds to be given to cash starved institutions devoted to tackling the problem. However, in becoming attuned over the years to responding to organised crime and trafficking with the firm iron fist of prohibition and military power the international is on the brink of beginning another perpetual conflict. In order to reverse the trend that is occurring the root causes of poaching must be analysed further; inequality, disenfranchisement, weak legislative and judicial structures and a lack of opportunities all have a significant part to play. It is essential to learn from the war on drugs so that the same mistakes are not repeated. For many of the species there will not be a fifty year learning curve available to do so. By maintaining a militarised response to wildlife trafficking the international community may be writing a new chapter in the history of failed global prohibition regimes.

Sean Mowbray is a freelance writer and blogger. A graduate of History and International Relations from the University of Dundee his interests lie in organised crime, particularly of an environmental nature.