Regime preservation in Central Asia

For elites in Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan, regime preservation is priority number one. Even if that means cozying up to Putin.

| Suggested Reading | Conflict Background | GCCT |

By Luca Anceschi

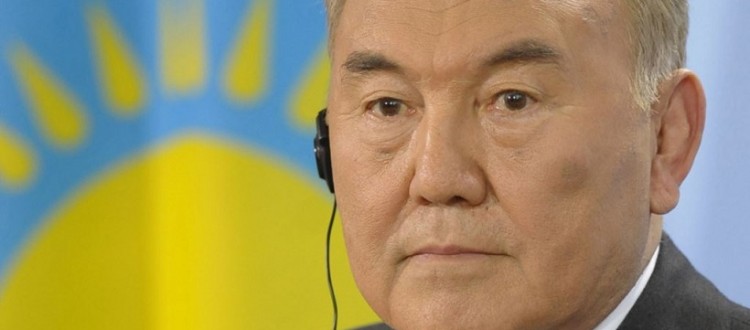

On 29 March, the citizens of Uzbekistan will visit polling stations around the country to elect the president of their republic. As per the non-democratic praxis to which Uzbek politics has conformed since the early 1990s, the electoral outcome has already been pre-determined, with incumbent president Islam A. Karimov certain to be returned to office for another term. Neighbouring Kazakhstan is also well on the way to re-electing its leader for another five-year term: the regime is expected to organise a snap election in the autumn of 2015, to re-confirm Nursultan A. Nazarbaev as president of the republic, which he has led since its independence.

Holding elections at semi-regular intervals may well be a nod to those sectors of the ‘international community’, which are willing to believe in Tashkent’s and Astana’s commitment to political liberalisation.The predictable landslide victories of the incumbents, however, ought not to be taken at face value: the presidents’ internal support is not as monolithic as post-election data will inevitably attempt to suggest. In the highly personalised political systems led by Karimov and Nazarbaev, elections have been reduced to a routine chapter in the local authoritarian practice, and, as a consequence, no longer represent the barometer of the leaderships’ internal support. But internal support is not entirely necessary to ensure regime preservation.

Regime backing

The very issue of regime backing, ultimately, is crucial to the crystallisation of authoritarianism in post-Soviet Central Asia, where the support/repression nexus has come to underpin regime relations with two key domestic constituencies. A strategy of systematic oppression – as recently underlined by Human Rights Watch – established (and eventually preserved) regime control over the local populations. And a mix of shrewd deal-making and ruthless retribution has, on the other hand, regulated Central Asia’s intra-elite relations, which have been transformed into a depressing competition for the cadres’ proximity to the leaders.

There is a third dimension to regime backing in Central Asia, and it relates in turn to the political linkages forged by the Central Asian regimes with key international actors. The external dimension of the support-building strategies devised by the regional elites – and the long-term regimes in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan in particular – represents in this sense the direct result of the leaderships’ ability to navigate the region’s complex geopolitics.

Karimov and Nazarbaev approached the Great Powers (the Russian Federationin primis and, to a lesser extent, China and the United States) through the alternation of entangling and dis-entangling strategies, to ultimately establish equidistant relations – and not mere clientele ties – with Moscow, Beijing, and Washington. While multi-vectorism and hyper-active diplomacy dominated Kazakhstani foreign policy for much of the post-Soviet era, Uzbekistan’s international activity oscillated on the other hand between partial isolation and timid engagement. If Kazakhstan’s and Uzbekistan’s international postures adopted a very different outlook, they did ultimately share an identical end, with foreign policy being elevated to a key role in the power technologies designed in Astana and Tashkent.

Pro-Russia manoeuvrings

The dramatic events that re-shaped Eurasian geopolitics in 2014, however, forced Central Asia’s senior leaders to question a fundament element in their support-building strategies. In the aftermath of the annexation of Crimea and the eruption of the conflict in eastern Ukraine, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan had to rethink their engagement with Vladimir Putin’s Kremlin. While designing the necessary new strategies to approach Russia in 2014, Kazakhstani and Uzbek foreign policy-makers faced a policy conundrum as they had to reconcile the identification of suitable responses to the Kremlin’s renewed assertiveness in Eurasia, with the short-term outlook of ageing presidents with no demonstrated interest in pre-arranged transfers of power. It was within this claustrophobic environment – which was happening against the backdrop of an economic crisis, which, in turn, is undoubtedly eroding the regimes’ domestic support – that Kazakhstani and Uzbek foreign policy had to operate in the post-Crimea months.

Both continuity and change were delivered by the choices made in Astana and Tashkent. The persistence of regime preservation as a key foreign policy determinant ensured that, in post-Crimea Eurasia, both Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan continued to pursue essentially domestic ends while simultaneously moving on the international stage. Policy change, on the other hand, was subtle, yet by no means insignificant: both regimes, at the end of 2014, had engaged in some markedly pro-Russia manoeuvres. The timing of this policy shift might appear puzzling, given the mounting international isolation that is surrounding the Kremlin, but it has to be regarded as fundamentally consistent with the power dynamics of ageing leadership in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan.

Uzbekistan

In Uzbekistan, the shift occurred as Russia’s political support came to be seen as beneficial to the authoritarian stability of the regime in Tashkent: similar considerations led, in December 2014, to a visible rapprochement between Karimov and Putin. Specifically, the finalisation of a rather comprehensive agreement – which included a substantive military package and the cancellation of Uzbekistan’s debt with Russia – opened an unprecedentedly positive chapter in what has traditionally been a tense relationship. As its finalisation took place, framed by a protracted intra-elite struggle, the 2014 agreement holds some significant relevance for Uzbek domestic politics. Good ties with Putin are certainly viewed as beneficial for long-term stability by those segments of the elite, which, reportedly, are expected to acquire a more prominent role vis-à-vis succession during Karimov’s next term in office. The Uzbek leadership, both current and prospective, formulated, in this sense, a positive assessment of the contribution that an improved relationship with Moscow might make to the regime’s short- and mid-term stability. This is not to say that Uzbekistan, in early 2015, has entered an exclusive clientele relationship with the Kremlin: the recent finalisation of the much-scrutinised military deal with the United States realigned the Uzbek foreign policy practice back to its customary balancing inclination.

Kazakhstan

In Kazakhstan, the elite concluded, not without some reluctance, that a less intense relationship with Moscow was indeed detrimental to regime stability. It is through this essentially domestic lens that we need to analyse the unprecedentedly pro-Russia policies put in place by Astana in the last 12 months. Kazakhstan’s abstention on the UN vote on the Crimea annexation, Nazarbaev’s unconvincing intransigence on EEU accession and negotiations, and his inconclusive quarrelling with Putin over Kazakh sovereignty show that multi-vectorism might ultimately be a thing of the past. In the late Nazarbaev era, Astana is unlikely to challenge Russia’s re-acquired control of Eurasian integrationism, as Kazakhstan will remain firmly anchored to the increasingly irrelevant EEU – an institutional framework which, six weeks after its formal establishment, has lost all its politico-economic significance. Kazakhstan’s foreign policy is therefore in a geopolitical cul-de-sac. But did it get there only due to Russia’s unrelenting pressure?

The reasons for the apparent end of multi-vectorism, are predominantly domestic. The Kazakhstani leadership, in this context, demonstrated some familiarity with the scenario, which led to the 2010 Kyrgyz revolution: a regime that is slowly becoming unpopular at home does probably need a powerful external backer, however unpleasant he (Putin) might be.

Nazarbaev’s internal support, to all intents and purposes, is on a declining curve: while Kazakh nationalists are expressing increasing unease for the leadership’s pro-Russia policies, matters of economic consideration are likely to further erode regime support amongst Kazakhstan’s rising middle class. There is an economic storm brewing: the tenge’s poor performance, the Kashagan disaster, and low oil prices will continue to affect negatively the Kazakhstani economy, affecting quite dramatically the living standards of urbanised segments of the population. The regime has to date failed to formulate a conclusive response to this impending crisis: while the articulation of the Nurly Zhol economic stimulus programme suggested that massive spending was seen as the preferred solution, recent policies revealed the rising popularity, amongst key government circles, of more austerity-centred economic measures.

The side-effects of Russia’s economic meltdown are also being felt in the less globalised economic landscape of Uzbekistan, where the amount of money that migrant workers are remitting has drastically decreased throughout the last quarter.

The Twilight zone

The patterns through which Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan moved closer to Moscow in 2014 might have been opposite in nature, but they appeared to be thoroughly consistent with the power strategies of leaders who, due to advancing age, have entered the final stage of their political careers. This reading of the recent evolution of the relations between Astana/Tashkent and Moscow confirms once again that Central Asia’s linkages with the Great Powers has continued to be dominated by the narrow, pragmatic interests of the local elites. For Kazakhstan’s and Uzbekistan’s elderly authoritarian leaders, the support of a more aggressive, decisively neo-imperial Kremlin is a welcome development: this is another indicator that the ‘soon-to-be re-elected’ Nazarbaev and Karimov have entered, in political terms, their Twilight zone.

Luca Anceschi is Lecturer in Central Asian Studies at the University of Glasgow. Follow him on twitter @anceschistan

This article was originally published by OpenDemocracy and is available by clicking here.

Regime preservation in Central Asia – TransConflict – http://t.co/BUeMKc2yqw

RT @MikeHitchen: Regime preservation in Central Asia – TransConflict – http://t.co/BUeMKc2yqw

RT @TransConflict: Regime preservation in Central #Asia: For elites in #Uzbekistan and #Kazakhstan, regime preservation – http://t.co/y6TQg…

Regime preservation in Central Asia – TransConflict – http://t.co/MIAfDLj39K

Regime preservation in Central Asia http://t.co/bZGG7GUjIv #Nonprofit