Mixed messages – what now for justice in Sri Lanka?

One would not offer therapy, shelter, or legal redress, to the victim of arson until one had first put out the flames. So to for Sri Lanka’s war survivors. The question of what form of justice mechanism Sri Lanka needs must eventually be answered. But the fact that the atmosphere in the north and east of Sri Lanka is too dark for such a process to even begin demands urgent attention.

| Suggested Reading | Conflict Background | GCCT |

By the Sri Lanka Campaign for Peace and Justice

It has been a confusing couple of weeks for those following Sri Lanka’s delicate progress back towards peace. Sri Lanka’s President gave two perplexing interviews in which he made troubling and factually inaccurate statements about how Sri Lanka is intending to deal with the past. His Prime Minister also made public comments, firstly seeming to contradict him, then seeming to support him. In the midst of all this, a visit from the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights came and went with surprising smoothness.

Now that the dust has settled somewhat, we attempt to pick through what was said and make sense of it all. What emerges is very worrying for Sri Lanka’s future, but not yet unsalvageable.

What was said

Many comments were made over the last couple of weeks by different people in different languages. It is important to look in detail at what was said and meant on each of these occasions.

The controversy started on January 22nd with an interview that President Sirisena gave to the BBC in Sinhala. You can read a transcript here and watch President Sirisena’s telling body language here.

Echoing a theme to which he would return several times over the next few weeks, he said that there was no need for international involvement in Sri Lanka’s special court for war crimes as Sri Lanka had all the necessary expertise and knowledge to conduct proceedings themselves. He was also seen shaking his head at the notion of the “hybrid court”- an arrangement involving a combination of international and Sri Lankan judges which was proposed by the United Nations and agreed to by the Sri Lankan government at the Human Rights Council session in September. Any notion that these were off the cuff remarks seemed to be dispelled when his official Twitter account made a point of tweeting out the video followed by the line “international interference is not needed”.

The President appeared to be directly contradicted by his Prime Minister a few days later when the latter gave an interview in English to Channel 4 News. You can watch it here.

Prime Minister Wickremesinghe seemed to leave the door open for international involvement in a justice mechanism when he said “we have not ruled that out” and then twice denied, in the face of evidence to the contrary, that President Sirisena had in fact done so.

Wickremesinghe’s interview was also notable in that he repeated remarks he first made at Jaffna Pongol celebrations that most of Sri Lanka’s missing were very probably dead. This seemed to be based on his view that six years has passed since the war’s end, and in light of the fact that he is only aware of 217 people detained under the Prevention of Terrorism Act or rehabilitation orders, it is very likely that anyone else who went missing while in detention is now dead.

Whatever one’s view on the likelihood of truth in this statement, its delivery on an auspicious day, and with no regard for the management of the mental health of the families of the disappeared for whom hope continues to be an important coping mechanism, was deeply insensitive. It will have come as a devastating blow to the many families who have spent many years testifying before, and seeking answers from, the various bodies established by the government to investigate missing persons.

Furthermore, if Prime Minister Wickremesinghe is correct, the logical conclusion that would follow would be that many tens of thousands of people died while in Governmental custody. Yet his response did not show a level of concern appropriate to that conclusion. Nor did he explain how the existence of secret detention facilities, at least one of which has now been uncovered, fits with his conclusions.

President Siresena spoke on the issue again in a longer television interview in Sinhala (with English subtitles) for Al Jazeera which you can watch here.

In an extraordinary thirty minute interview President Sirisena first spoke candidly about the state of the Sri Lankan economy, and the fact that Sri Lankan Government will be very dependent upon the support of the international community. He then spoke at length about war crimes, making a number of basic errors from which it is impossible to draw any conclusion other than that this is an issue that he clearly hasn’t been following very closely. In particular:

- He stated that the United Nations investigation (the “OISL” report) makes no mention of war crimes but “only” human rights violations. In actuality what the OISL report said was:

“The sheer number of allegations, their gravity, recurrence and the similarities in their modus operandi, as well as the consistent pattern of conduct they indicate, all point towards system crimes. While it has not always been possible to establish the identity of those responsible for these serious alleged violations, these findings demonstrate that there are reasonable grounds to believe that gross violations of international human rights law, serious violations of international humanitarian law and international crimes were committed by all parties during the period under investigation.” (p. 217)

This is as close to stating that war crimes took place as a report with OISL’s mandate can get.

The President then repeatedly stated that the Human Rights Council exonerated Sri Lanka of war crimes charges. In fact the Human Rights Council, with Sri Lanka’s backing, passed a resolution calling for a special court to be set up to look at war crimes charges.

- He stated that the “Paranagama commission report” makes no mention of war crimes. When it was pointed out to him that it in fact did, he denied that it was an official government report, despite the fact that its mandate was extended by his own Government.

- He once again firmly rejected the need for international involvement in the justice mechanism, and seemed to suggest that it was not called for in the Human Rights Council resolution his Government cosponsored, despite the fact the resolution clearly:

“…affirms in this regard the importance of participation in a Sri Lankan judicial mechanism, including the special counsel’s office, of Commonwealth and other foreign judges, defence lawyers and authorized prosecutors and investigators.”(paragraph 6).

This time around he was not contradicted by Prime Minister Wickremesinghe, and it was even reported that the Prime Minister endorsed his argument, telling parliament that the “constitution does not permit foreign judges to sit in judgment”. However a closer reading of his comments suggest that what the Prime Minister was actually saying was simply that implementing the UN’s recommendations might require Sri Lanka’s constitution to be amended – and that the Supreme Court would need to decide on the issue. Even if such a change were required, since the Government is in the middle of amending its constitution, this presumably is not a significant hurdle.

Who is in charge?

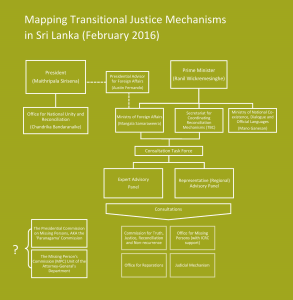

Part of the confusion and contradiction stems from the difficulty of knowing who is in charge of Sri Lanka’s reconciliation process. There are two branches of Government and four different Governmental departments involved. They have established three different consultation mechanisms to advise on the make up of the four forthcoming implementation processes. Even discounting advisors and various other offices which will play a key role (such as the Attorney General’s office) that means that Sri Lanka’s reconciliation process has at least 11 moving parts. We try to make sense of who does what, in the following infographic:

Complicated as this may be, it is clear that in general this process will be run by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, with oversight from the Prime Minister’s office. The President will only be indirectly involved.

This however should not be taken to mean that the President’s opinion does not matter, nor that his remarks can be disregarded. Sri Lanka’s very recent past illustrates the potential for Presidential power to disrupt peace processes. Many will remember in particular the 2002-2005 peace process, where the international community and progressive elements within Sri Lanka worked to build peace with a seemingly more amenable Prime Minister (Wickremesinghe once again) while ignoring and isolating a more recalcitrant President (previously Kumaratunge), with the end result that the President became suspicious of the entire process and eventually destroyed it. It is vitally important that supporters of a sustainable peace in Sri Lanka continue to engage with President Sirisena, and bring him along with them. Clearly this has not been happening.

Still unclear is how any of the processes above relate to the “Paranagama Commission”; a Presidential commission first tasked to investigate missing persons and subsequently war crimes. With no formal role within the process, widely discredited with respect to both mandates, and boycotted by survivors’ groups, the Paranagama commission’s lack of future should be clear. Yet inexplicably, its mandate has once again been extended.

Also not featuring in discussions is the fact that Sri Lanka already has an Office of Missing Persons: the Missing Persons Commission (MPC) unit of the Attorney General’s department. This office however appears to be entirely dormant.

Another matter for regret is that the Office of National Dialogue under Mano Ganesan appears to be largely sidelined. In our research on war survivor’s needs and expectations from the reconciliation process his name came up frequently, unprompted, as one of the few members of the Sri Lankan Government in whom survivors placed confidence and trust.

The international response, and the path to peace

The international response to President Sirisena’s comments has been muted but negative. America’s ambassador to the Human Rights Council quickly clarified that international involvement in Sri Lanka’s justice process was a vital part of the package that Sri Lanka agreed to in September.

In a diplomatic but strong statement on his visit to Colombo, UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein also made the same point.

But the reason why international involvement in Sri Lanka’s justice mechanism is so pressing is not just that its absence would place Sri Lanka on a collision course with the UN and the international community. Far more important is that Sri Lanka can only know a lasting peace if it ends its culture of impunity and the cycles of violence it feeds. Both the war affected community and international justice experts have made it clear that this can only happen with international involvement.

The Government of Sri Lanka may argue with some justification that international involvement in a justice mechanism is domestically unpalatable, and that they are bound by the wishes of their electorate. However this is a problem partly of their own making. The Government of Sri Lanka has shown no leadership on the reconciliation issue, and has been nothing but defensive when it comes to the need for a justice mechanism. The Sri Lankan public can be forgiven for not comprehending the need for a process their own Government appears to be ashamed of. A change of attitude is needed; the Government of Sri Lanka needs to explain to the public why the peace and stability of the island depends upon this process.

How might the government now move forwards given the difficult bind that President Sirisena’s unfortunate comments have now placed them in? One way out of the corner they have forced themselves into would be to commit firmly to the just-launched consultation process on transitional justice and to refrain from further pre-judging of its outcomes.

Such a consultation will almost certainly reveal the complete lack of trust war affected communities have in a domestic justice process. This would allow President Sirisena to truthfully say that while his opinion on the competence of Sri Lanka’s domestic justice mechanism to function effectively remain unaltered, in order for the survivor community to have a greater trust in the process, he will allow international involvement.

Priorities and sequencing

One of the most unfortunate aspects of the President and Prime Minister’s comments is that it has focussed international attention on the justice element of the path back towards peace, whereas sequentially, there are many other elements which need to be in place before this can happen. A justice mechanism must not be rushed, and must be allowed to mature from consultation with survivors. It would be highly regrettable if international pressure caused the Government of Sri Lanka to prematurely announce a flawed mechanism.

Instead, international pressure and Government actions should be focussed upon creating a conducive atmosphere for trust in the transitional justice process: by bringing an end to ongoing human rights violations and the constant surveillance of northern and eastern civil society, by ending the military’s involvement in civilian and economic life which many see as a form of economic warfare on the civilian population of the north and east, and by engaging in trust building measures such as returning land occupied by the military, releasing the final batch of detained LTTE cadres, and abolishing the hated Prevention of Terrorism Act.

Recently our Campaign Director was discussing the reconciliation process with a war affected group in northern Sri Lanka. The “four pillars” of reconciliation (truth, justice, compensation and apology) were discussed. Then one of those present said “but before any of this, we want the Government to stop doing it. What use is an apology when it is still happening?” This sums up the mood of many of Sri Lanka’s war survivors in the north and east of the country. Looking at Sri Lanka’s path back towards peace they do not think Sri Lanka is yet at the point of the question of national reconciliation, but is still on the previous step: bringing an end to the violence which, while becoming more subtle with the change of Government, still has not drawn to a close.

One would not offer therapy, shelter, or legal redress, to the victim of arson until one had first put out the flames. So to for Sri Lanka’s war survivors. The question of what form of justice mechanism Sri Lanka needs must eventually be answered. But the fact that the atmosphere in the north and east of Sri Lanka is too dark for such a process to even begin demands urgent attention.

The Sri Lanka Campaign for Peace and Justice is a multi-ethnic, non-partisan group who campaign for a just and lasting peace in Sri Lanka, based upon accountability and respect for human rights.

The Sri Lanka Campaign for Peace and Justice is a member of the Global Coalition for Conflict Transformation, which is comprised of organizations committed to upholding and implementing the Principles of Conflict Transformation.

This article was originally published on the Sri Lanka Campaign’s website and is available by clicking here. The views expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect the views of TransConflict.