Militarisation in Sri Lanka’s north – not going away

Two recent reports show how the Sri Lankan military is continuing to weave itself into the fabric of everyday life in the north, including through the continued growth in military-run businesses, the control of private investment, and – perhaps most unsettling of all – the direct co-option of vast numbers of local people through their recruitment into the Civil Security Department (CSD), a military operated economic development provider involved in running farms and pre-schools.

| Suggested Reading | Conflict Background | GCCT |

By the Sri Lanka Campaign for Peace and Justice

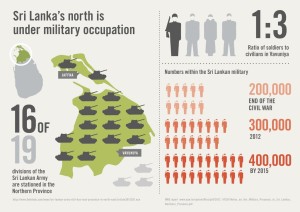

In 2013, four years after the bloody final stages of Sri Lanka’s civil war, we produced a series of infographics detailing the chilling extent of the military’s presence in the North of Sri Lanka. Those infographics painted a picture of a country a long way from sustainable peace,despite the absence of war. Army personnel were not only occupying vast swathes of land in vast numbers, with dire human rights consequences for those living there; they also appeared to be part of an an active effort by the then government to assert control over all aspects of economic, social and civic life in Tamil majority areas.

Following the surprise defeat of former President Rajapaksa in January 2015, things were meant to change and, for a time at least, the new government seemed to be moving in the right direction. Public commitments to the restoration of normal civilian life in the former conflict zone were followed by the return of several pockets of land to their rightful owners. A number of key military checkpoints were dismantled. And the visible presence of khaki in the streets appeared to decline significantly.

Following the surprise defeat of former President Rajapaksa in January 2015, things were meant to change and, for a time at least, the new government seemed to be moving in the right direction. Public commitments to the restoration of normal civilian life in the former conflict zone were followed by the return of several pockets of land to their rightful owners. A number of key military checkpoints were dismantled. And the visible presence of khaki in the streets appeared to decline significantly.

Long tentacles, tight grip

Yet two reports released last week, authored by ACPR and PEARL (available here and here), give lie to the perception that Sri Lanka’s North is successfully de-militarising [1]. Indeed, many of statistics that they present are just as, if not more, alarming than those we highlighted four years ago, despite the various government commitments to change that have been made since.

One of the stand-out figures we cited then was an estimate that in some parts of the North, soldiers numbered civilians at a ratio of 1:3. The latest statistics in these reports suggest that ratio may now be as high as 1:2 in places, with as many as 60,000 soldiers stationed among a population of just 130,000 in Mullaitivu, the epicentre of the very last days of the war. Expressed another way, 25% of the entire Sri Lankan army is currently deployed in an area inhabited by just 0.6% of the Sri Lankan population.

Even more concerning than the sheer numbers are the findings in the latest reports on how the military is continuing to weave itself into the fabric of everyday life the North, including through the continued growth in military-run businesses, the control of private investment, and – perhaps most unsettling of all – the direct co-option of vast numbers of local people through their recruitment into the Civil Security Department (CSD), a military operated economic development provider involved in running farms and pre-schools.

The consequences of these activities and initiatives are most obviously apparent in terms of their impact on local economies, with businesses unable to compete with artificially low-prices, and individuals who do turn to the military for their livelihoods forced into positions of dependency. Yet subtler and even more pernicious has been their impact on levels of community trust, political engagement and sense of identity: CSD farm employees are monitored constantly by intelligence officers; pre-school teachers are required to regularly report to military staff and provide updates on their activities; and the loyalty of children is cultivated through the distribution of uniform and gifts, as well as the frequent hosting of awards and sports ceremonies by senior army officials. In the words of one of the reports interviewees, people engage with the security forces out of necessity “but the army uses it as an opportunity to isolate that individual from the community”.

The consequences of these activities and initiatives are most obviously apparent in terms of their impact on local economies, with businesses unable to compete with artificially low-prices, and individuals who do turn to the military for their livelihoods forced into positions of dependency. Yet subtler and even more pernicious has been their impact on levels of community trust, political engagement and sense of identity: CSD farm employees are monitored constantly by intelligence officers; pre-school teachers are required to regularly report to military staff and provide updates on their activities; and the loyalty of children is cultivated through the distribution of uniform and gifts, as well as the frequent hosting of awards and sports ceremonies by senior army officials. In the words of one of the reports interviewees, people engage with the security forces out of necessity “but the army uses it as an opportunity to isolate that individual from the community”.

Leading by example

Looking ahead to March 2018, when the government will once again report to the UN Human Rights Council on its progress on post-war reconciliation, these reports provide a timely and important reminder of just how far the government has to travel in order to deliver on its commitment to de-militarisation – and to lay the foundations for a peace built on the confidence and trust of minority communities, rather than one held together by force and fear.

But they also raise pressing questions about the relationships that have developed between members of the international community and Sri Lanka’s armed forces under its new government, and whether sufficient priority has been given to the issue of de-militarisation in recent times. Why, for example, does the US military continue to host military photo-ops in Sri Lankan schools and participate in ceremonies on occupied lands despite fears about the way this legitimises the Sri Lankan army’s own encroachment into these spaces? Why has the UN invited Sri Lankan soldiers to participate in a peacekeeping mission in Mali despite the fact that none has been held criminally accountable for the child sex ring that operated during a previous mission in Haiti between 2004-2007? And why, despite repeatedly stated concerns about the lack of transparency, has the UK government not made available any monitoring and evaluation material concerning the impact of the £6.6 million it is currently spending on ‘security sector reform’ in Sri Lanka?

But they also raise pressing questions about the relationships that have developed between members of the international community and Sri Lanka’s armed forces under its new government, and whether sufficient priority has been given to the issue of de-militarisation in recent times. Why, for example, does the US military continue to host military photo-ops in Sri Lankan schools and participate in ceremonies on occupied lands despite fears about the way this legitimises the Sri Lankan army’s own encroachment into these spaces? Why has the UN invited Sri Lankan soldiers to participate in a peacekeeping mission in Mali despite the fact that none has been held criminally accountable for the child sex ring that operated during a previous mission in Haiti between 2004-2007? And why, despite repeatedly stated concerns about the lack of transparency, has the UK government not made available any monitoring and evaluation material concerning the impact of the £6.6 million it is currently spending on ‘security sector reform’ in Sri Lanka?

The answers to these questions have, to date, been largely unsatisfactory. They suggest that while the government of Sri Lanka bears primary responsibility for failing to grasp the nettle of de-militarisation, members of the international community are themselves falling well short in terms of how they are using their influence, leverage, and technical assistance to bring pressure to bear on this issue. Unless the goal of reducing the military’s extraordinarily tight grip over Sri Lanka’s North is placed front and centre within strategies for engagement, it is they too who run the risk – as these latest reports suggest – of ‘normalizing the abnormal’. High time for a re-think.

The Sri Lanka Campaign for Peace and Justice is a member of the Global Coalition for Conflict Transformation, which is comprised of organizations committed to upholding and implementing the Principles of Conflict Transformation.

This article was originally published on the Sri Lanka Campaign website and is available by clicking here. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of TransConflict.

Footnote

- The Adayaalam Centre for Policy Research (ACPR) is a not-for-profit think-tank based in Jaffna. People for Equality and Relief in Lanka (PEARL) is a Tamil advocacy group, based in Washington DC. ‘Civil Security Department: The Deep Militarisation of the Vanni’ was produced by ACPR. ‘Normalising the Abnormal: The Militarisation of Mullaitivu District’ was produced jointly by ACPR and PEARL.

Pingback : October 2017 Review - TransConflict