Why grassroots peacebuilding? Is ‘inclusive peacebuilding’ a more sustainable recipe for peace?

The Colombian Peace Agreement (CPA) is known as being the most inclusive peace deal to date, as several civil society organizations partook in the negotiation process and helped in drafting the final agreement. Two years later into the peacebuilding process, how inclusive is the implementation of Colombia’s peace?

| Suggested Reading | Conflict Background | GCCT |

By Marthe Hiev Hamidi

Recognizing the ineffectiveness of propagating a liberal, one-size-fits-all approach to peacebuilding, western states, developmental NGOs and international financial bodies are gradually moving away from implementing top-down peace-interventions in post-conflict societies that reflect the ‘Western’ norms (like democracy, a liberal market-economy, human rights and the rule of law). Instead, the popularity of communitarian/grassroots ways of peacebuilding is growing amongst international peace practitioners. The grassroots approach considers peacebuilding a bottom-up process that focuses on integrating the community level.

In 2012, peace scholar Desirée Nilsson presented the results of a ground-breaking quantitative study of over 80 peace agreements from the post-Cold War period. Interestingly, Nilsson (2012) found that the durability of peace is significantly increased when Civil Society Organizations (CSOs) are included in peace settlements. Nilsson ascribes this result to the possibility that the inclusion of CSOs in the peace agreement strengthens the ‘legitimacy of the peace process’, thereby referring to local ownership of the peacebuilding process.

In grassroots peacebuilding, local ownership implies that peace processes are designed, managed and implemented by local actors rather than by external actors. The objective of grassroots peacebuilding is to contribute to national peacebuilding policies through local knowledge. The grassroots approach – if implemented correctly – could propagate a more inclusive and sustainable approach to building peace than the liberal way of doing so by top-down intervention.

How ‘locally owned’ is Colombia’s Peace?

Although the CPA of 2016 marked the official end to a civil conflict that lasted for over half a century, causing 220,000 deaths, 43,000 disappeared persons and about 6 million displaced people [3] – the work had only just begun. The Final Agreement includes settlements between both sides on the future political participation of FARC members, rebels’ reintegration into civilian life, the eradication of illegal coca-crops, transitional justice and reparations for victims, the disarmament of rebels and the implementation of the peace.

Consisting of 297 pages, the final version of the CPA is lauded to be the most inclusive peace agreement to date, setting a global precedent for inclusion and political participation of historically marginalized groups, particularly women, indigenous peoples, Afro-Colombians and the LGBTI communities. Colombian CSOs were able to substantially influence the peace process during the negotiation phase.

During the negotiation phase, a Gender sub-Commission was initiated upon demand of several grassroots initiatives, which led to the creation of the first peace agreement with a gender focus. Similarly, an Ethnic Commission was created on behalf of several ethnic CSOs (vouching for the rights of indigenous, Afro-Colombian and other ethnic groups) and eventually managed to include an ethnic chapter guiding the interpretation and implementation of the agreement.

When the CPA was signed in 2016, many grassroots initiatives in Colombia continued with their peacebuilding practices, albeit in a new context of national peacebuilding policies. To assess how grassroots peacebuilding relates to the CPA, two examples of good practice would be: the Peace Community of San José de Apartadó and the Colombian NGO Corporación Descontaminá.

Colombian grassroots peacebuilding in the implementation-phase

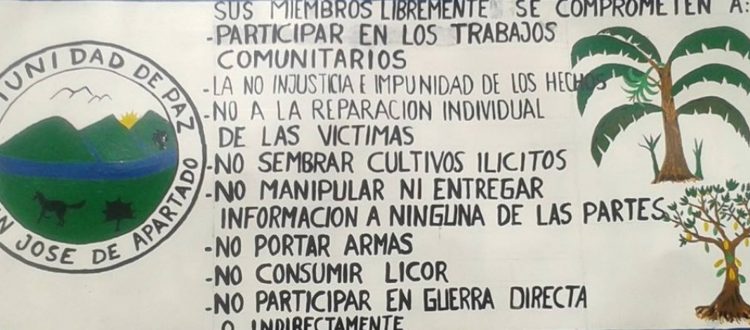

In 1997, the Peace Community of San José de Apartadó was formed by a community of 500 peasant farmers in the war-torn region of Urabá. The collective declared itself neutral in the on-going civil war, even though the farmers were (and are still) facing grave threats because of the many economic interests in their land and continued presence of guerrillas and paramilitary groups.

Today, the Peace community is a self-governing group of approximately 1,000 members that propagates citizen participation as a way of peaceful resistance to the conflict. They use external resources for their own benefit without surrendering authority for decision-making: the farmers can bring cases against combatants through the Inter-American Court of Human Rights to raise awareness and discourage future attacks. In this respect, the Peace Community serves as a prime example of ‘hybrid’ peacebuilding – a combination of grassroots peacebuilding and liberal peacebuilding.

The signing of CPA has led to new threats for this peacebuilding initiative, as paramilitaries have taking advantage of the power vacuum left by the exit of the FARC in November 2016 and the sparse presence of the State in the region. It is this lack of state protection that discourages the multiplication of similar grassroots initiatives, which are capable of successfully realizing citizen participation and thus help to transform conflict by propagating an inclusive and non-violent approach.

The Colombian NGO Corporación Descontamina is another grassroots initiative that operates in Bucaramanga, a city in the Andes Mountains. This NGO seeks to address the inability of state-led DDR (Demobilization, Disarmament and Reintegration) programs to meet the basic necessities for demobilized people, like insufficient access to psychological support. Corporación Descontamina organizes local projects to promote non-violent communication and psychological support in a men’s jail where ex-paramilitaries and ex-guerrilla’s live together.

Moreover, Corporación Descontamina fulfils an important role by stepping into the DDR process, where some problems are harder to solve because of a lack of trust in the government as a former party to the conflict. Due to the state’s involvement in the conflict, state-driven DDR processes in Colombia have been hindered by political polarization. Drawing from this example, grassroots initiatives can be a powerful tool for informally filling the gaps in the peacebuilding process – that might otherwise be badly addressed through the formal framework provided by the CPA.

Colombian peace – how to move forward?

To strengthen the peacebuilding process in Colombia, (inter)national peace practitioners should be aware of the potential power of grassroots initiatives, which can be at the forefront of their own peacebuilding efforts and explores ways to connect with the local voices in what can be called a ‘hybrid’ approach to peacebuilding. This would allow both the national and the local level to fill gaps in the peacebuilding process, such as the lack of citizen participation or the need for sustainable funding.

Inclusivity and knowledge-exchange remain important centrepieces of the peacebuilding process; it is exactly in this respect that grassroots initiatives and CSOs need to be more present and supported in the implementation of peace, both at the national level and by international community. Moving from the peace deal to a stable and inclusive peace in Colombia means that an important role is reserved for those who are able to identify gaps in the implementation of the CPA. By connecting and streamlining the different existing approaches to peacebuilding, and ensuring that local voices are included in national processes, it might be possible to build a peace that is more comprehensive and sustainable for all Colombians.

Marthe Hiev Hamidi is an MA Student of Peace and Conflict Research, with a keen interest in local peace building initiatives. She’s currently in Colombia doing field research on peacebuilding practices with indigenous ex-combatants in the Cauca region.

This piece was originally published by Peace Insight and is available by clicking here. The views expressed in this piece do not necessarily reflect those of TransConflict.