Sovereignty for Metohija

Treat the Serbian Orthodox Church as a respected partner in a comprehensive, single-stage agreement on the status of Kosovo.

| Suggested Reading | Collaborate | GCCT |

By David B. Kanin

I have written before on this website about the “Michael Collins problem,” the danger of assassination faced by people courageous enough to strike a deal with adversaries in an identity or sovereignty conflict. Collins, who resisted leading Irish Republican negotiations with the British, was assassinated during a civil war fought between advocates and adversaries of the deal he struck for the creation of an Irish free State that left out Ulster. Similarly, Israel’s Yitzhak Rabin was murdered by a Zionist fanatic who opposed compromise and the Oslo Accords. Arafat himself survived that compromise but opponents organized a rejectionist front within the PLO. It remains unclear whether those who attempted to murder Kiro Gligorov – who survived a car bombing after he included ethnic Albanian politicians in what eventually became the consociational arrangement that continues to govern North Macedonia – had motivations similar to the people who killed Collins and Rabin.

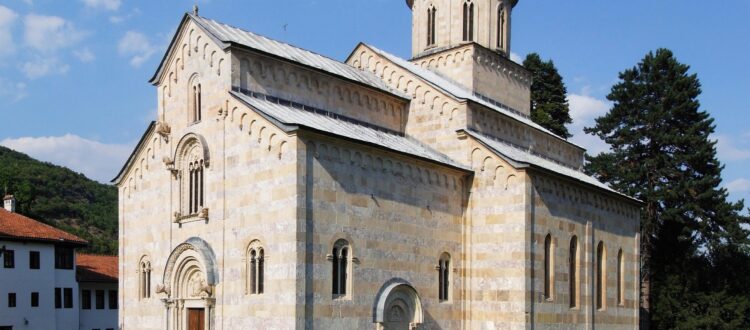

Any agreement designed to end the bitter, ongoing conflict over the stunted sovereignty of Kosovo will produce the same dangers to the people on both sides who strike a deal. Therefore, future negotiators should treat the problem of dealing with lethal spoilers as a central component of the implementation and intercommunal engagement processes involved in any agreement. One important actor in this process has been, is, and will be the Serbian Orthodox Church (SPC). The Church owns the spiritual properties that provide physical evidence of ties between Serbian identity and the lost province – the use of the term “Metohija” in official Serbian nomenclature reflects the palpable, spiritual, and historical aspects of Serbia’s claim on Kosovo. SPC hierarchs have been in the forefront of efforts to draw international attention to alleged Kosovar crimes against Serbs and to promote the case that Serbian sovereignty over Kosovo is a diachronic fact and synchronic necessity.

The SPC also serves as a lodestar for many nationalists who reject any compromise on Kosovo – a point central to the thesis of this essay. Reducing SPC opposition to the sovereignty of a largely Albanian Kosova would undercut some of the domestic legitimacy of hardliners who use SPC-based symbolism to sanctify their unalterable opposition to anything short of Serbian reabsorption of the whole of Kosovo.

It might be worth proposing the creation of something like the Vatican mini-state that since the 1929 concordat between the Catholic Church and Mussolini has defined the relationship between the Church and the Italian state. The two situations are not entirely analogous, of course. Unlike Kosovo, Italy had long been a universally recognized state – it was the Church not the state that required definition of its physical and political status. There was no ethnic component to the problem because everyone involved (including the Pope) was Italian.

Nevertheless, creation of a formally recognized state of Metohija as part of deal under which Serbia recognizes Kosovo might undermine the solidity of SPC opposition to acknowledging the loss of a 90 percent Albanian entity. The SPC would be guaranteed control over the security of and access to Serbian spiritual centers. It not only would maintain ownership and administrative fiat, but Belgrade would finance the construction of new protected highways running between Serbia and the sites in Metohija and among those sites as well. Not every Serbian Orthodox Church in Kosovo would be part of Metohija. Nevertheless, even those that are not would be guaranteed tithing rights, control over religious education, and other functions similar to the conditions that existed after the Ottomans granted the SPC autochthonous distance from the Ecumenical Patriarchate in 1830. Serbian security personnel would serve the functions of the Vatican’s Swiss (and other) guards. Metohija would join the United Nations at the same time as Kosovo.

It would be a mistake to underestimate the durability of the SPC’s clout or dismiss the Church as a backward, anachronistic relic in a supposed age of liberal institutionalism and secular, multiethnic states. Teleology is as much a factor in such thinking as in religious belief and obstructs useful analysis and policy formation. The complacent mismanagement of the SPC in Montenegro by Milo Djukanovic is an object lesson worth taking to heart. Greater respect for the central role of the SPC in Kosovo might have helped Washington avoid the miscalculations and poor policy planning that created Kosovo’s current contested status between 2006 and 2008.

Of course, it also would be a mistake to assume the creation of a state of Metohija would completely remove opposition to Kosovar sovereignty from some SPC hierarchs and priests. Hardline nationalists would continue to use religious symbolism in their protests and a few diehards would resort to violent attacks on those willing to work toward an agreement. Still, speaking as directly as possible to the specific demands of the SPC in and about Metohija might be a way to reduce the numbers and influence of the spoilers who are sure to assault those with the courage to strike a deal.

Mutual recognition of the separate states of Kosovo and Metohija by Belgrade and Pristina would be productive only if folded in to a single comprehensive agreement on status and bilateral relations. This is the only way to avoid the mistake made by EU Balkan mavens when they forced Kosovo to accept a one-sided “dialogue” in April 2013 intended to create a Community of Serbian Municipalities in Kosovo without deciding the status of Kosovo itself. Albin Kurti, unlike his predecessors (and, perhaps, his successors) is acting in his country’s interests by refusing to accept the nonsense that agreements on technical issues and establishing institutional legitimacy for a resoundingly Serbian association in Kosovo supposedly integrated into Kosovo’s institutions would mark progress toward peace and reconciliation. The highly touted establishment of the Dialogue has enabled Belgrade to preach “status neutrality” and play the part of a mature partner willing to consider compromise – knowing full well that Serbia would continue to command the loyalty of the municipalities comprising any CSM while Pristina would continue to lack the sovereign status necessary to enter the EU and UN.

There is no low-hanging fruit when it comes to existential conflicts over status and identity. There are no guarantees that a first agreement over a slice of such conflicts will lead to a promised second set of negotiations. Settling the Kosovo imbroglio without another round of fighting will happen only if one deal is struck that treats all major factors in the dispute. The interests of the SPC make up a central piece of that mosaic.

David B. Kanin is an adjunct professor of international relations at Johns Hopkins University and a former senior intelligence analyst for the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA).

The views expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect those of TransConflict.

Photograph by Pudelek (Marcin Szala) – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0.