Addressing the culture of violence in Kenya

TransConflict is pleased to present a two-part analysis of the drivers of conflict in Kenya, focusing initially on the need for restorative justice – particularly where land matters are concerned – in order to address the emerging culture of violence.

Suggested Reading |

Conflict Background |

GCCT |

By Kisuke Ndiku

This analysis is based on the author’s personal experience and observations as a peace practitioner. It is the author’s view that truth without justice is lame – as is justice without truth – and leads only to punitive and ineffective reconciliation. Many observers of Kenya’s history are aware of occurrences of violence that have either remained silent or have been documented by committees and commissions, yet the findings continue to lie in filing cabinets or on the shelves of governments and civil society alike. As Kenya enters its Jubilee year, its leaders should commit to never again allow the country to fall back into violence and anarchy. This can only be achieved through restorative justice to address the culture of violence. The concept of restorative justice needs to be explored, explained and disseminated to peacebuilders and practitioners of conflict transformation.

In many respect, Kenyans have never had the time to stop and ask the hard questions, such as why its citizens are increasingly intolerant of one other, fifty years after independence? Why do we invade our neighbours’ cattle? Why do we force neighbours out of land they have lived on all their lives? Why do citizens pay so dearly for land issues and associated injustices? Why do we not combat impunity and corruption, but instead allow them to eat away at our liberties?

History speaks to Kenya – “Look for pathways towards peaceful co-existence”

After the struggle for independence, occurrences of violence have defined periods of political and electoral campaigning. My own neighbour was killed because he supported a candidate who did not get “imprisoned by colonialists in the agitation for uhuru”. The voter died, not the candidate vying to be elected. Another group of neighbours were embroiled in the ‘Shifta war’, with soldiers and many of my own people killed. The amnesty may have led to a cessation of hostilities, but the cause of the Shifta war was not resolved in a just manner.

In the political arena – starting from the colonial times to date – various key persons were eliminated in acts of violence. In addition, many Kenyans were subjected to detention because of their political causes. Civil society organizations, particularly faith-based organizations, have over time – through their lobbying and advocacy – continually raised the point that human rights should be upheld. Many different Committees or commissions of enquiry have been set up, but often without successes in resolving the issues they were tasked with resolving. Ordinary citizens continued to suffer acts of violence and injustice in new unprecedented ways due to their political stances. This seems to have given birth to political intolerance in Kenya and led to one-partyism in 1982.

During every election period since 1987, a similar situation has occurred in the pursuit of multi-party democracy. Many families lost more than just their property; they lost their loved ones and the lives that were built over many years. By and large, young people in Kenya are the fodder during politically-related violence. It is not enough to simply state that, due to joblessness or under-employment, they accept to act upon payment. It is important to find out why they make that choice in view of the circumstances they face, particularly those of personal dehumanization and feelings of betrayal and desperation, which seem to trigger desires for revenge. The fact that society has not found a vent for such experiences is in itself a root cause of a culture of violence.

Conflict transformation

Violence is violence in any name. For any people to live with a culture of violence is bad enough. Violence raises profound questions about how to transform conflict so that communities can live in peace. Unless both victims and perpetrators are transformed, there will be no end to violence. It is, therefore, imperative for peace practitioners – and their partners – to consider strategies emanating from the concept of conflict transformation. Within this paradigm, local communities work together to end violence and conflict. In the words of young people from Jos, Nigeria, people have to reach the point where they decide to begin “refusing to be enemies”. Conflict transformation has to do with making choices and taking new positions on issues that divide a people.

Restorative justice

An important concept in dealing with the nature of conflict in Kenya is restorative justice. When people question and fight over identities, when they struggle with injustices and inequalities – both actual and perceived – rooted in the past, and when a nation suffers structural injustice and inequality, restorative justice is the proposition best suited to addressing the situation.

Restorative justice engages local communities in the process of seeking solutions to their predicament, which in the Kenyan case is a culture of violence. Yet contained within it is the provision for saving face whilst providing justice for wrong doings – a basis for restoring relations. Restorative justice does not conflict with formal law, but possesses advantages over the machinery of formal law by incorporating local communities at all levels; often proving more time- and cost-effective. It has proved to be more successful in resolving local conflicts compared to parliamentary commissions or tribunals, as evidenced by the Potok Marakwet and Turkana community conflicts.

Conflict trends

Why are communities in Kenya, on the one hand, regarded as “peace lovers”, and on the other, as people inclined towards a culture of violence? One response to this is that justice has not been delivered. At the same time, violence opened the space for future conflict; conflicts which were not adequately addressed when they occurred. Based on natural law, justice is perceived as a value and virtue upheld by all. For justice to be achieved, it has to be acceptable; for justice to be acceptable, it needs to be seen as an enforceable principle by both contesting sides. For justice to be enforceable, equality should be upheld.

Law and justice enforcers should focus on equality and demonstrate fairness in how justice is dispensed. Justice and equality should also be timely. There are numerous instances of delayed justice in Kenya. It is not enough to say that the courts are overwhelmed; the judiciary cannot be expected to be solely responsible for dealing with cases of delayed justice. New venues have to be brought into play if future violence is to be addressed, and communities need to address these issues themselves, immediately and directly. This is one way justice and peace can be restored. Restorative justice can thus become a viable option. It is known that communities have their own means and ways of dealing with such issues, as they have successfully addressed the matters they deemed important. This has been demonstrated by the use of ‘Amani Mashinani’ (‘Peace in the Grassroots’) Approach, advocated and elaborately used by Bishop Cornelius Korir of the Catholic Diocese of Eldoret.

Intolerance as a threat to peace

Group demonstrations demanding action of one kind or another is often seen as a barometer of tolerance or its lack thereof. If, for instance, children would take to streets tomorrow demanding action of one form or another, it is likely that violence would ensue. Since all public gatherings or demonstrations require permits and a police presence to maintain security, law and order, there is always a possibility of confrontation with citizens. For instance, if a lone stone-thrower who is not even taking part in the demonstration interferes, this could trigger confrontations between demonstrators and law enforcement agencies. The stone-thrower could, for instance, target security guards, who would in turn blow a whistle to stop the demonstrations; thereby prompting confusion, stampedes and possible deaths. Unrelated to such demonstrations is the looting which often occurs when confusion ensues. Though unrelated to the aforementioned demonstration, such looting is likely to be associated by the law enforcement agencies acting to restore order; leading to street battles and other forms of tension.

This example depicts the strained relations existing between law enforcement agencies and ordinary citizens. By the end of such events, the matter for which the demonstration was intended gets coloured, if not entirely covered. Indeed, during occurrences of violence, many inflict violence on people they know personally. Politicians have mastered the art of contextual association, particularly with the young, with the intention of exploiting the situation for personal gain.

Years of not finding justice

In earlier acts of politically-related violence – such as the 2007/2008 incidents in Mt Elgon, Kisumu, Burnt Forest, Kuresoi, Molo, Naivasha, Likoni and Changamwe – women and girls were not involved directly. However, the role which families play, plus the level at which individual families are affected, cannot be left ignored. One could speculate that many young people, especially women, had experienced similar violent incidents before. They therefore saw no reason to sit back at a time when upheavals were taking place. The acts of 2007/2008 define the emergence of a culture of violence which was borne out of years of unfulfilled justice. Certain communities in Kenya have repeatedly tried to call for justice, but as recent media coverage demonstrates many cases remain unresolved.

Not ethnic violence, but a culture of violence

In the wake of the 2007/2008 violence, a new theme emerged – namely, that violence was accepted. The media quickly served-up ‘the happy’ few who had looted and joyfully waved weapons in the streets and villages. The media and several observers talked about “ethnic violence taking place in Kenya”, with some defining it as “land clashes”. This was as unwittingly negative as it was far from the truth. Some notable personalities even went as far as to refer to those events as being equivalent to ethnic cleansing. However, students and practitioners of peacebuilding quickly pointed out that it would be very difficult to describe those events as tribal or ethnic conflict, or even genocide, as some termed it.

The National Council of Churches, the oldest faith-based entity, the Kenya Episcopal Conference and Islamic entities, human rights agencies and others who responded to the aftermath of conflict have over the past five years carried out assessments, baseline studies, evaluations and recorded stories of the causes of violence. None has come-up with evidence that violence was triggered because of ethnicity. Instead, they have amassed evidence that inadequate employment opportunities for youth, especially young males, better explains the violence. In addition, almost all reports call for greater attention to social, economic and political injustices which need to be addressed.

Land defines the identities of communities

One form of injustice concerns the lack of involvement of local citizens on issues directly affecting them, particularly those concerning land and other commonly-shared resources. Land as a factor of the struggle for independence has a lot of emotional attachment to all communities in Kenya, defining their respective identities. Closely-related to land are administrative and political boundaries.

All communities in Kenya prior to colonial times defined themselves as a people to whom nature/God bequeathed a particular geographical location. Land was therefore communally owned. In this connection, borders, boundaries, surveys, survey maps and title deeds are foreign in this definition of a people. Part of the injustice of modern Kenya, therefore, is the failure to address the historical definition of the identities of communities in relation to land.

Land clashes as a misnomer

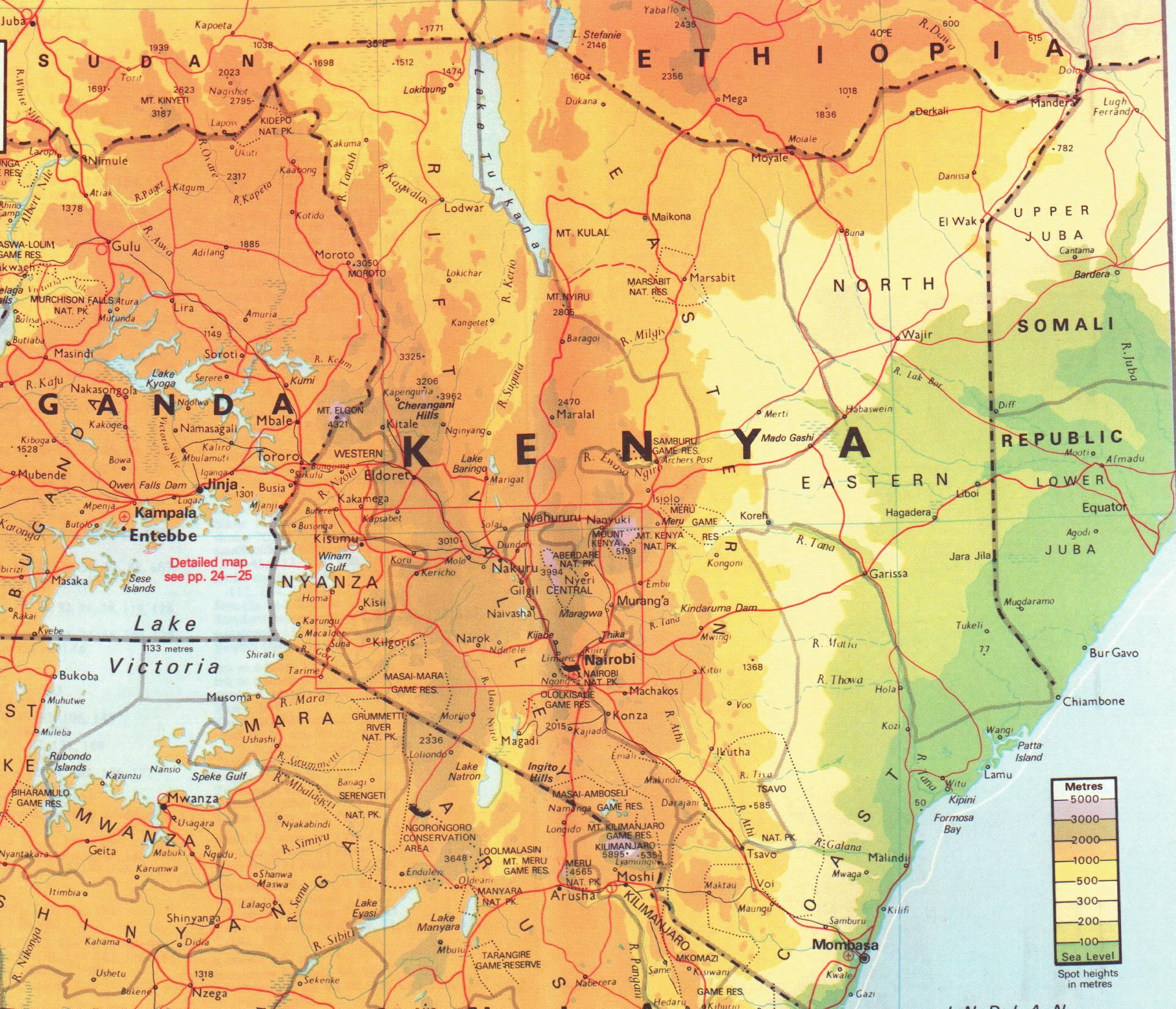

There were no land clashes in Kenya and there has never been land clashes either. The term “land clashes”, as used in the media, is misleading. Land itself cannot clash with people, though it is true that people can clash over land. Land defines the identity of a community. By distributing land without a due process of consultation with local communities, a sense of injustice – one that is often manipulated – has remained. This defines the basis of the issues raised from the Coast in Mombasa and Tana, to Mountt Elgon; from Lake Turkana to Lake Magadi; from Mui Kitui to the Taita iron ore mines. Such issues are defined by unvoiced grievances pertaining to what is seen as an unfair distribution of natural resources and land that should be commonly-shared.

This introduces the notion of equity in resource allocation and distribution, even where money to buy and willingness to sell is concerned. The colonial regime did not last very long; before a generation had passed, Kenya had attained independence. Communities knew then, as they do now, that ancestral land was taken unfairly by colonial powers. At the time of independence, it was expected by all communities that their land would revert back to them. This was, however, never to be. This has left a complex of unmet expectations in different communities, the most significant being the Coastal Areas, the Rift Valley and the Mount Elgon areas.

Communities in these localities continue to sense inequity and injustice as far as land issues are concerned. They perceive that their identity has been interfered with. Opening dialogue on such matters is required if the wounds are to be healed. Without dialogue, there cannot be a resolution. It is not enough to state that those who got or bought land simply have it. Dialogue is needed to secure an equitable resolution of this matter; only restorative justice can deal resolutely with such issues.

As long as historical matters of land remain contentious, the question of community identity will remain uncertain. As a result, unwieldy politicians will whip-up those elements of identity and violence will repeatedly occur; violence which tends to increase in size and intensity each subsequent cycle. Violence occurs not because of land clashes, but because of the identities of people who have been treated unjustly; with strengthened perceptions of inequities that drive fear, suspicion and mistrust, thereby fracturing peaceful co-existence. Furthermore, new issues such as the exploration and mining of valued resources increasingly enter the land equation.

Political violence and the identities of communities

One factor of political violence has been the identities of communities; hence such remarks as “how is Kenya?”, which communities of the east, north east, north and north west would ask when visited by a person from other localities. A more recent assertion is “Pwani si Kenya” (coastal localities are not part of Kenya), another statement of identity by communities. These facts cannot be ignored given the evolution of the politics of land and borders.

The communities of the Central Counties in Kenya – plus parts of the Elgon, Rift Valley and south eastern Kenya – were deprived of their own homelands during colonial times. These were converted into either game parks, nature reserves or white highlands (for tea, coffee, livestock, wheat and maize plantations). At the advent of independence, they could not return and simply re-occupy the same lands that their fathers and fore fathers inhabited. This aspect of colonial history was never addressed, nor was the internal political displacement which forced communities into concentration camps. Local communities to whom lands belonged were never consulted. Instead a regime of cooperative and settlement farms was created, with many community members from the central counties settling in Elgon, Rift Valley, Mwea, Taita, Tana River, etc. Those who had power, position and money obtained large tracts of land. Over time, and due to changing economic fortunes, land has been divided, sub-divided and re-sold.

In conclusion, political violence has attained a land dimension due to the manner in which land was acquired – without due consultation, nor reference to historical factors. The same goes for land which was formerly used by pastoral communities, especially those in the Right Valley and North Eastern locations of Mount Kenya. Indeed, it is noteworthy that in the central counties there has never the kind of violent upheaval by the communities in those areas characterized as flashpoints of political violence in Kenya.

Kisuke Ndiku is the executive director of Active Non-Violence Initiatives Kenya, a member of the Global Coalition for Conflict Transformation.

Very interesting article. I had a slightly different impression of the different dynamics that are taking place in Kenya (particularly in the Rift Valley) in relation to conflict, with land being one of the major problems. Perhaps the author (and other users) might be interested in reading my article here: http://www.opendemocracy.net/opensecurity/valentina-ba%C3%BA/five-years-on-identity-and-kenyas-post-election-violence

I do find very important, though, the issue of youth unemployment and discontent, which leads young men to be easily manipulated in joining gangs or other groups that engage in a violent response to the situation.

Pingback : The inaugural GCCT newsletter | TransConflict

Education for peace and civic values should be targeted. Suggested reading:

Finkel et al. 2012. Civic Education and Democratic Backsliding in the Wake of Kenya’s post-2007 Election Violence, Journal of Politics.