Building an organic dialogue process in Kashmir

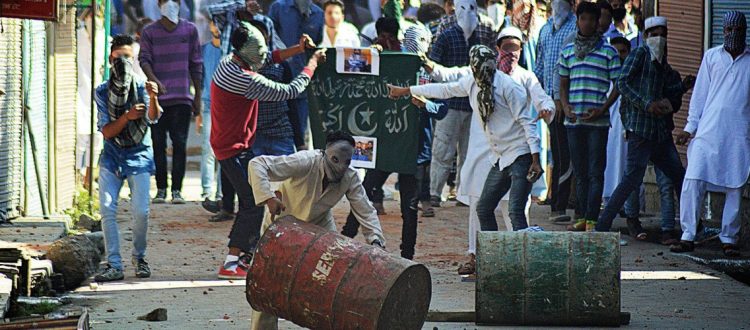

A new round of dialogue and political engagement has been launched in Jammu and Kashmir. Despite some boycotts, a large number of stakeholders are involved. This process is taking place at a time of broader tensions in Kashmir Valley where an increasingly radicalised youth and active terrorism threatens to spiral the situation out of control. In this context, can an organic dialogue take root?

| Suggested Reading | Conflict Background | GCCT |

By Ashima Kaul

The much-awaited ‘dialogue and political engagement by central government of India’ has started in Jammu and Kashmir. After a stressful period of violent protests, the blinding of youth in Kashmir, barbaric killings and lynching’s, hard military offensives on terrorist groups and a financial clamp down on separatists through raids by the National Investigative Agency, once again a new attempt is being explored to broker peace in the state.

However, ground dynamics and the nature of the conflict present the greatest challenge since 1990. This is because the radicalization of young people has found roots in the minds of a large section of Kashmiri youth, and the political endgame envisioned by people of the three regions – including Kashmiri Pandits in exile – presents contrasting and conflicting futures.

Boycotts and mixed perspectives

While the Joint Resistance Leadership, an amalgamation of separatist parties and organizations, has rejected the dialogue offer and boycotted any talks with the interlocutor, Dineshwar Sharma, over 60 delegations across the political and regional spectrum have met him over the course of three rounds of consultations that took place in North and South Kashmir.

There are mixed reactions to the renewed dialogue process. “It is a futile exercise without engaging with the Hurriyat,” said Bilal Bashir Bhat, founder and treasurer of the Jammu and Kashmir Young Journalists Association. According to him, 120 members of the Association had different personal opinions with some wanting to participate in the process; nonetheless, they boycotted the talks. “We held a meeting which was perhaps influenced by the Hurriyat decision. As such we failed to arrive to a consensus in order to go and meet the interlocutor.”

Understandably, it is not easy to publicly go against the “political sentiment and ideology generated by separatists over the years.” However, contrary to the ‘projected perception’, the ground sentiment was in favour of the dialogue and people wanted the Hurriyat to engage with them. Their boycott has disappointed many and the process is now perceived as ‘being reduced to a formality’, a mere ‘token exercise’, ‘buying time’, not being serious or an ‘eye wash’.

“The real core political issue is the Kashmir issue. The delegations that went to meet the interlocutor only presented their personal grievances and issues but not any political issues because none of them have the mandate. Hurriyat draws a popular mandate and has a public influence,” says Bhat. “Therefore, Hurriyat’s participation in the dialogue is a must and the government must think of creative ways to involve them in the process,” Bhat added.

Expressing a different perspective, a local journalist under conditions of anonymity opined that it is a misperception that if the Hurriyat would not participate, a ‘real’ political process will not be underway. In a candid conversation with him he continued, “the truth is that the nature of the movement has radically changed over the past decade – more so after the Burhan Wani episode. It is not in the control of the Hurriyat anymore. Its strings and control are elsewhere.”

Clearly, he was referring to the terrorist/jihadi groups that are operational in Kashmir Valley, the ideologues who speak from mosques or the agitated, and the aggressive and emotional youth on the ground leading street violence and agitation. “Whether the Hurriyat participates or not is not relevant. The bigger question is, will its participation really make a difference? If not, then where is the leadership to direct change,” the journalist concluded.

A looming threat fills the vacuum

Indeed, there is a leadership vacuum. The arm-twisting that the government is exercising with the Hurriyat is a political game that many do not understand or connect with. Ordinary people, mothers, workers and college students, daily wage earners or traders, financial or educational institutions, are all more interested in a ‘faith assurance’ from the government that their interests, insecurities and fears will be addressed and protected. In the absence of ‘mutual faith’, separatists and ideological constituencies play on people’s emotions. The government should directly meet the people and listen to them. The only antidote to radicalisation and disconnect is to connect at the grassroots level.

Another challenge for the government is Kashmir’s rather perplexing reality. It is not only about the deepening radicalisation of youth in Kashmir Valley but also how this narrative has emerged as the dominant one. While it is difficult to scale the physical presence of ISIS, it cannot be denied that its ideology has found a home in Kashmir.

However, this alone is not the story of Kashmir. The sad part is that the alternate story is not making the headlines. Hence even when a 23-year-old Sajid Yousaf, founder of the Jammu and Kashmir Youth Alliance and a pro-India voice, reaches out to engage with the interlocutor, the story of a 20-year-old footballer, Majid Khan, from the Sadiqabad colony in the South Kashmir district of Anantnag that has joined Lashkar –e- Taiba, a terrorist organization operating in Jammu and Kashmir, made more headline news and captured the psyche of Kashmiri youth.

The state police fears that youth like Majid could be used as ‘pied pipers’ to lure youth to the ‘jihad factory’ and join the ranks of terrorists waging a war against India. Majid, however, under emotional pressure from his mother’s appeal for him to come back, responded to her and on November 17, 2017, returned to his family through the help of the local state police and the Indian Army.

Social media sites erupted in celebration of ‘Majid’s homecoming’, certainly a win-situation for the government and security forces. But voices who advocate for peace are against violence live in constant fear. “We feel vulnerable for sticking our necks out. The government needs to protect and empower those who are questioning the ideology of Azadi and the violence that is being perpetuated in its name, and resist all separatist politics,” Yousaf said.

A new voice among Kashmiri youth

There is a new youth leadership which seems to be struggling to emerge from the ‘suffocating’ environment of ‘dehshat and siyasat’ (terror and politics). “There is a youth constituency emerging that wants to resolve conflict through discourse and dialogue,” said Touseef Raina, founder of the Global Youth Foundation. He added, “I met the interlocutor to discuss street violence, shutdowns which affect education and businesses, the issue of passports for former stone pelters, the Agenda of Alliance and governance.” Both Yousaf and Raina advocate non-violence and dialogue for the resolution of the conflict. “It is our youth who are dying, hence it is our problem to bring a shift in mindset,” Raina asserted.

“Is enough being done to empower such voices,” added the journalist. “It is extremely difficult. The opportunity has been missed. We have spiraled down. The family-, social-, institutional fabric are in crisis in Kashmir, and there is a deep trust deficit where the use of pellet guns has deeply angered the people.” For young people like Yousaf and Touseef who are struggling to create civic spaces at the peril of personal safety, it is razor’s edge walk. It is between those who should be stopped from indoctrination to such voices and the vulnerabilities that major groundwork needs to be covered by the government in order to ensure a positive result.

The reality on the ground

Scepticism about the sincerity of the dialogue is not only noticeable in Kashmir Valley. Many hold similar concerns and views in Jammu communities, including exiled Kashmiri Pandits. “Jammu’s identity and its place in history as the seat of the Dogra empire since 1947 has been undermined and over-shadowed by the Kashmir-centric populist narrative,” said Manu Khajuria Singh, founder of Voice of Dogra. “The discontent and youth radicalization in Kashmir Valley certainly needs to be addressed, but as far as the ‘Jammu and Kashmir issue’ is concerned, people of Jammu are equal stakeholders to the conflict,” she said ruefully and added, “to the chagrin of the people of both regions, they have been deviously pitched against each other by invoking Islamist and nationalist identities. Hence people in Jammu Kashmir are suspicious about the intent of the dialogue when there has been no groundwork done to create trust between them.”

People do not have trust because for two decades there have been many attempts which have not been followed up or sustained. “People have doubts,” said Professor A. N. Sadhu, an eminent Kashmiri Pandit who is an educator and social activist. While many observers and a large section of the people in Jammu and Kashmir firmly believe that only dialogue and discourse will transform and resolve the conflict, the memory of past initiatives, from the dialogue of the Planning Commission’s chairman K. C. Pant in 2001 to Prime Minister Manmohan Singh’s roundtables in 2007 and the 2010 appointment of Radha Kumar, Dilip Padgaonkar and M.M. Ansari as interlocutors, have not produced major results. “We feel that no outsider can resolve the conflict within. Only an organic leadership and dialogue will be able to produce results,” Sadhu asserted. Khajuria agrees as well to the internal dialogue approach. “We need to set our house in order, listen to each other and find a solution.”

According to the South Asia Terrorism Portal in 2017, casualties related to terrorism have escalated to much higher figures than in past years. As of November 2017, there have been 54 civilian deaths and 71 security personnel deaths, and 185 terrorist/militants have been killed in encounters with security forces. The figures, however, do not reveal the social and political dynamics of the conflict. Conflicting perspectives and antagonistic narratives of self-determination fuel identity and justice binaries in Jammu and Kashmir. They require a serious reflection on how to engage at the grassroots-level for a new political space to emerge in the region which addresses these grave polarities. Otherwise, the potential reality is that Kashmir may become a dangerous jihadi den where the borders along the Line of Control continue to be exploited, and the Kashmiri Pandit community continues to live in exile and people in Kashmir Valley face daily violence and live under oppressive draconian laws.

Sadly, there does not seem to be any sense of relief. Will the new dialogue process change anything on ground? Will the new youth leadership strike back through innovative ideas, challenge violent extremism and become a cross–regional chord that pushes the organic dialogue process to take root? It will not only require time but also the wisdom of the government in truly empowering these individuals. This is what will make the difference.

Ashima Kaul coordinates the organisation Yakjah in their work in Jammu and Kashmir. An independent journalist by profession, she has an active interest in interfaith dialogue.

This article was originally published by PeaceInsight and is available by clicking here. The views presented in this piece do not necessarily reflect those of TransConflict.